Translated by Liza Thomas

———————————————————

We reached Coimbatore by 5 p.m. on Day 7. Booking a hotel adjacent to the Corporation Bus Station proved to be a disaster. Though it was right in front of us, it was located on a one way street. We had to navigate through traffic for nearly half an hour to enter its basement parking. However, amidst this hassle, we identified a few likely eateries to have dinner. After dinner, we worked late into the night on the travelogue.

Publishing the travelogue is a relatively simple process. Producing the video, is an entirely different ball game altogether. Stabilization, exporting, uploading etc takes four to five hours or more depending on network conditions. By next morning we managed to publish the video. We left Coimbatore soon after having breakfast.

We were on the way to Nilambur, via Anaikatti, Agali, Attappadi, and Mannarkkad. After driving a few kilometres through the rush of Coimbatore town, we entered a highway flanked by Royal-Poinciana (locally known as Gulmohar) trees in full bloom. The road was enflamed in their fallen red blossoms.

The all pervasive western ghats were visible on either sides as we passed through. In the valley, we spotted quite a few brick kilns similar to the ones we had seen on the way from Aralvaimozhi. The kilns here had tall, steel smokestacks. From a distance, these looked like cell phone towers or wind turbines without blades.

Road conditions were perfect when we started the ascent to Anaikatti. But I didn’t feel like speeding up. The spectacular views on both sides deserved to be savoured. Frequent signages indicating elephant crossings were a constant reminder that we were passing through pachyderm territory. Travellers driving from Kerala to Coimbatore should definitely take this route once in a while.

After Anaikatti, road conditions quickly deteriorated. And that, usually, is an indication that you have crossed over to Kerala from Tamil Nadu. I would not recommend driving all the way to Mannarkkad on this miserable road. We had lunch at Mannarkkad and reached Nilambur by 3:00 p.m. The agenda for the day was to visit the Teak Museum. I had been to the museum earlier in 2009 with my friends from Nilambur Sali, Sabu and Naseer. However, Johar was visiting it for the first time.

The pathway to the entrance is overhung by tall ‘Indian Thorny Bamboo’. There is plenty of parking space available (parking fee is ₹25 per vehicle) inside the museum campus. Entry fee is ₹50 per person, and ₹300 per camera.

A huge teak tree stump including its complex root cluster is displayed at the entrance to the museum. This root cluster was dug up from the Kuritti beat (a forest range is divided into several administrative areas called “beat”) in the Nilambur Forest Rage. One of the characteristics of teak is that, as the tree ages, the tap root shrinks away, leaving a huge cluster of lateral and oblique roots. This can be seen in the root cluster on display. Visitors are required to remove their footwear before entering the building.

The huge ornamental door of the museum, made entirely of teak wood, is befittingly magnificent for a museum of this nature. The museum is a treasure trove of all sorts of fascinating information on Teak. The English word ‘Teak’ originates from the Tamil word ‘Thekku’. Teak belongs to the genus Tectona. The word Tectona is derived from the Greek word tektōn, which means ‘carpenter’. Tectona grandis is the species commonly found in India. The two other significant species of the genus are Tectona hamiltoniana and Tectona philippinensis, both found in Southeast Asian countries including Myanmar and Philippines.

The museum showcases everything about Teak, from planting, to logging, milling, and woodworking. Teak was exported in large quantities from the Malabar region in ancient times. Historical documents detail the process by which logs for export were transported to port cities through inland waterways (a network of canals, estuaries and rivers connecting inland areas to the sea). During colonial times, teak was extensively used for shipbuilding, and logs were sourced from natural forests. The advent of railways further increased the use of teak, and it soon became scarce. The British were quick to realise that the only way to ensure a regular supply of teak was to create teak plantations in the forests.

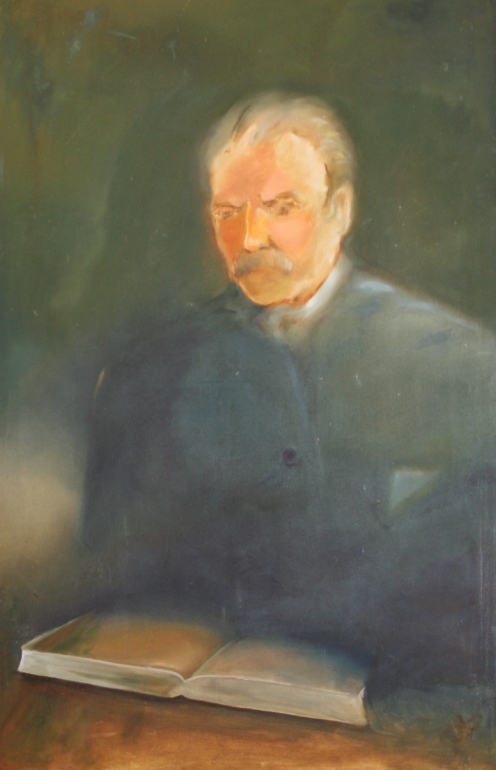

One of the most important names in the annals of Teak history in India, is that of Thomas Fulton Bourdillon. This Englishman served as the Forest Conservator of Travancore (an erstwhile princely state which is now part of Kerala) from 1891 to 1909. During his conservatorship 6,793 hectares of teak plantations were laid out. Bourdillon is credited with evolving a new propagation technique for teak – planting moderately hard stem cuttings. The ‘Bourdillon Teak Forest’ in Aryankavu of Kollam district is named after him.

A giant 116 year old teak tree, obtained from the Valluvassery beat is one of the main attractions of the museum. 38 metres tall, with a girth of 3.90 metres, the tree had to be cut in two in order to be brought into the museum.

Saplings are planted 2 metres apart. Later on, less healthy saplings are culled to allow more room for growth. In Kerala, harvesting/logging is done in 50 to 80 years.

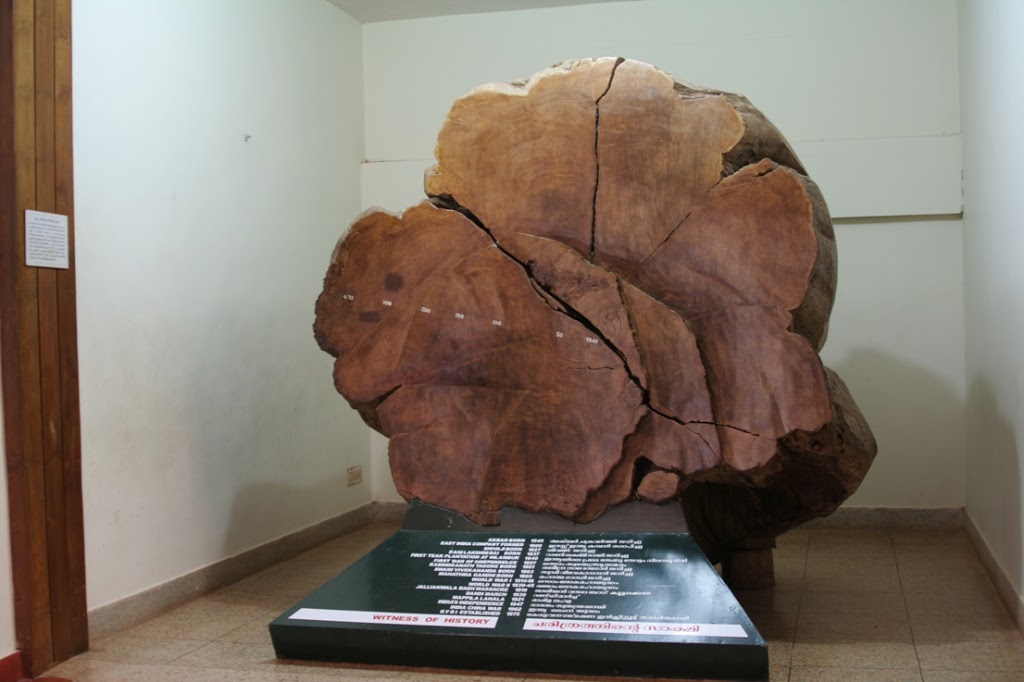

A cross section of a 452 year old Teak tree planted in 1542 is preserved in the museum. The tree was cut from Nakarampara range of the Kottayam Forest Division in 1994. The trunk was 20.40 Metres long, and was auctioned for one million Rupees at the Thalacode Depot. It is astonishing to think that this tree was planted in the year that Emperor Akbar was born, and it was 405 years old when India became independent. This is not a sight you get to see everyday. This tree has witnessed more history than I have ever read.

Every aspect of teak cultivation – propagation methods including cloning, grafting, and tissue-culture, irrigation, common diseases and pests affecting teak, other quality issues – is covered in detail in the exhibits.

One of the exhibits is a picture of the Connemara Teak Tree. Located in the Thunikkadavu range of Palakkad district’s Parambikulam division, this 500 years old teak tree is 49 metres tall and has a girth of 7 metres. The Connemara Teak tree has received the Mahavriksha Puraskar (Great/Giant Tree Award) instituted by the Indian Ministry of Environment and Forests. I remember trying to reach my arms around this tree when I visited Parambikulam years ago. The sensation was akin to hugging the Great Wall! A tourist visit to Parambikulam is incomplete without experiencing the Connemara teak.

Teak trees grow naturally in the deciduous forests of India, Myanmar, Lavos and Thailand. Additionally, due to being highly sought after in global markets, its grown in tree farms in around 40 countries. In fact it could possibly be the only tree of its size to be cultivated across national borders.

The individual who can be credited with ensuring Nilambur Teak’s place in history, is an Englishman named V.H. Conolly erstwhile Collector (district administrator) of Malabar. Under instructions from Conolly, Forest Conservator Mr.Chathu Menon established a Teak plantation known as the Connolly Plot. Today, this plot is one of the main tourist attractions of Nilambur. On my previous visit, I had crossed a hanging bridge over the Chaliyar River to visit this plot. We intend to visit the Connolly plot during GIE’s Kerala leg.

Once we completed our tour of the museum, we headed to the ‘bio-resources nature trail’ behind the museum building. The grove of trees I’d seen years ago had transformed into a veritable forest. The nature trail has areas dedicated to various botanical groups, including moss and algae. 10 years ago, this was where I learnt the astonishing fact that 90% of the world’s oxygen is produced by algae. Other sections of the nature trail include a Xerophyte (desert plant) and Succulent garden, a fernarium , and herbarium which contains over 180 species of herbs.

But the crowning glory of the nature trail is its butterfly garden. This is known to be the first butterfly garden in Kerala. This has been developed through the selective planting of flowering plants attractive to butterflies, and edible shrubs preferred by their larvae. The larvae of each butterfly species prefer to eat only a select set of shrubs and plant leaves. Butterflies feed on secretions from various parts of shrubs and trees including nectar from the flowers and juice of ripening fruit. While Lime trees, Royal Poinciana, Eshwaramooli, and Curry trees provide food for the larvae, flowering plants and shrubs like Lantana, Marigold, Zinnia, Ixora and Mussaenda are rich sources of nectar for the butterflies.

Even the butterfly garden had changed significantly. The entire garden was much more picturesque than it was 10 years ago. It would be easy to attract butterflies into our own gardens and backyards if we are able to recreate similar conditions. Johar was so excitedly capturing the garden from multiple angles that I was afraid he would get worn out. I was continuously clicking away as well. The garden offered splendid views, irrespective of which way the camera was pointed.

When GIE officially arrives in Nilambur, we plan to spend time capturing the garden in greater detail. Visiting time at the museum ends at 5:00 p.m. Our lodging for the night was already booked, and we started towards it. We were happy that the past two days were relatively free of issues.

We have almost completed our preparedness tests for GIE. The only equipment remaining to be tested is our tent. And that we plan to do tomorrow.

Edited by Nishad Kaippally

—————————————————————————–

Read the next part of this travelogue here.

View the YouTube Video of this travelogue here.

Read the original Malayalam text of this travelogue here.

Hear the Malayalam sound track of this travelogue here.