Translated by Liza Thomas

———————————————————

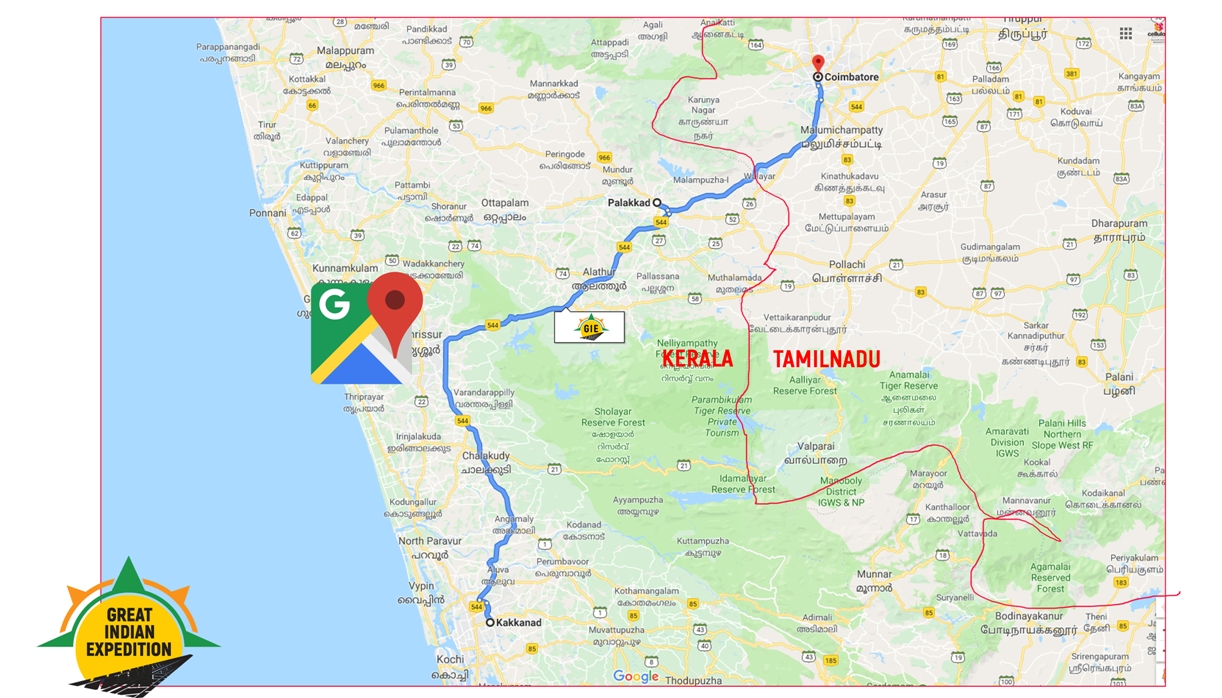

Part 2 of the Great Indian Expediton’s trial run started on May 30, 2019 from Ernakulam. Departing from Thrikkakara at 07:45 AM, we had breakfast at Angamaly. Our journey across the Western Ghats continued via Mannuthy and Kuthiran. This route through the hills doesn’t have any ‘hairpin’ turns. It’s one of the most commonly used passes across the western ghats. Consequently, heavy traffic congestions are quite frequent. In order to reduce the congestion, two 1-kilometre-long tunnels are being constructed through the ghats. However work on this project, which should have been executed a decade ago, is still underway with no end in sight.

When we reached Kuthiran, the route was relatively less congested. We stopped our vehicle to film the tunnels. Palakkad was another 47 kilometres away. The day’s destination was Palakkad Fort, otherwise known as Tipu’s Fort. While driving on the six lane highway, two cows dashed across the road right in front of our vehicle. I had become extra cautious as soon as I spotted the cows. An important advice I had received while discussing GIE with renowned traveller Baiju N. Nair, was to avoid causing any harm to cows. According to him, while travelling in North India, an accident involving a cow was likely to endanger the driver’s life. He had recounted an incident where he was involved in a similar situation, and was only able to escape unhurt from the clutches of a mob, because a police jeep happened to come by. GIE’s trial was proving to be a test run for such situations as well. Even without the additional aura of the ‘Gomatha’ (mother cow, considered sacred to Hindus in the northern parts of India) this docile animal was worthy of consideration as a living being. I had travelled to Palakkad -and through Palakkad to Bangalore, Chennai etc- countless times. However, I had never been to Palakkad Fort earlier.

The fort is located at the centre of Palakkad Town. Its location seemed to be similar to that of the Vadakkumnathan temple which is at the centre of Thrissur Town. This perception could have been caused by the fort’s elevated location and the road winding around it. We had to take a drive around the perimeter of the fort before we were able to locate the entrance. Parking is available on premises.

Around noon, with perfect lighting conditions for filming from any angle, we entered the fort with our gear. Entry passes were ₹ 25 per head. Though not being charged at the moment, rates for camera passes were also displayed. The fort proved to be well preserved and manicured. We encountered visitors of all age groups resting and conversing on the lawns surrounding the fort.

Even in peak summer, the water level in the moat surrounding the fort was reasonably high. A few workers were engaged in cleaning the moat. We committed the various exterior views of the fort to our minds and cameras, and entered the fort, crossing a bridge across the moat.

There is a Hanuman Temple inside the fort. The entry passes are verified only beyond this point, since visitors to the temple do not need passes. While researching the history of the fort, we found that most sources including Wikipedia list the fort as built in 1766 by Tipu Sultan’s father, Haidar Ali. The local ruler of Palakkad, commonly known as Palakkad Achan, was originally a dependant of the powerful ruler – the Zamorin of Calicut. When Palakkad Achan become independent of the Zamorin he sought Hyder Ali’s help to protect Palakkad against a likely invasion. Hyder Ali utilised the opportunity to gain control of Palakkad.

The control of the fort was held by the Mysore Sultans, the British, and by the Zamorin at various times in history. In 1784, the British are even said to have voluntarily given up control of the fort. From this chequered history, it’s obvious that the fort has borne witness to innumerable battles and bloodshed. The fort covers an area of approximately 60,000 m²

History is replete with inconsistencies, disagreements and ambiguity as far as Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan are concerned. As per the Archaeology Department’s information board, Hyder Ali renovated the fort after capturing Palakkad in 1776. Which means, the fort existed in 1766. However, the board does not provide any information regarding the original builders of the fort. From further enquiries, it was clear that a fort did exist here long before the 18th century. It was later renovated and expanded to its current grandeur by Hyder Ali.

A Taluk (sub district) Supply Office, and a Special District Jail (which houses around 200 convicts) are presently functioning within the fort. The process to relocate both to premises outside the fort is underway. The buildings will then be converted to offices for the Tourism Department. A few more government departments like Horticulture, and Land Reform also have their offices inside the fort. It is indeed interesting that the fort, which used to be the administrative headquarters of Malabar during ancient times, still houses government offices. Once these offices are relocated outside the fort, that too will become a part of history.

We found an old incinerator furnace inside the fort. It was almost 3 metres tall. We realised that it was being used to incinerate waste. This practice should definitely be stopped – if everyone starts burning waste, the resultant pollution would be huge. The ticket checker at the gate made tall claims of human bodies being burnt in the incinerator during colonial times. As with all local stories, this too should be taken with a pinch of salt.

There were quite a few visitors inside the fort ranging from groups of students to families. The fort was apparently a protector of romantically inclined couples as well. One of the main things about the fort which attracted my attention was the near perfect upkeep of the premises. However a few buildings, including the jail were showing signs of neglect. Hopefully this issue would be resolved soon as well. Unlike many other forts in the region, Palakkad Fort is primarily constructed using Granite blocks. While ancient brick and mortar form the upper section of the walls. Some of this brickwork is exposed to the elements now. There are massive bastions at all corners – a total of 7 large and two small ones. Except for a slight projection in front, the fort is almost a perfect square.

In peak summer, the greenery in and around the fort is soothing to the eyes. Centuries old Mango trees still survive inside the fort. A huge collapsed branch has almost re-grown into a seperate tree. The trunk of this tree alone covers around 400 m².

In February 2018, we had undertaken a week long journey to study and record the history of various forts from Kochi to Goa along the coast. That travelogue is still awaiting publication, in the form of a book titled “Katha Parayunna Kottakal” (Tell tale forts). Suddenly this experience felt like the continuation of that journey. The time was 02:00 PM, and the day was getting warmer by the minute. We left the fort after finding respite in a couple of glasses of Sambharam (spiced buttermilk) from a small kiosk near the Supply Office.

During lunch, we were accompanied by our Palakkad based friend Shaji Mulloorkkaran. Though constantly in touch online, it had been quite a few years since I met him in person. After lunch, we took leave of Mulloorkkaran and started towards Coimbatore where we planned to halt that night.

Edited by Nishad Kaippally

—————————————————————————————

Read the next part of this travelogue here.

View the YouTube Video of this travelogue here.

Read the original Malayalam text of this travelogue here.

Hear the Malayalam sound track of this travelogue here.