Translated by Liza Thomas

———————————————–

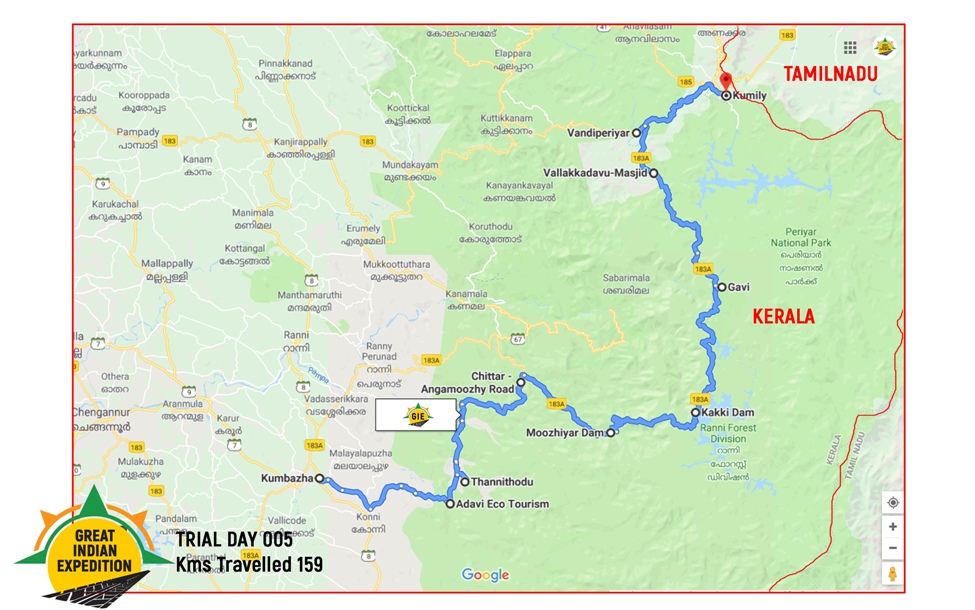

Day 4 ended at a Tourist-Home (Motel) in Kumbazha, a small town near Pathanamthitta. The plan for Day 5, was to travel through Gavi, up to Vandiperiyar. A forest department pass is required to enter Gavi and only a fixed number of vehicles are allowed in every day. Two wheelers and busses are not allowed. The only busses allowed to travel along this route are ‘Jungle Rider’ and ‘Gavi Boy’ operated by the Kerala State Road Transport Corporation (KSRTC).

Johar had inquired about the forest pass and area restrictions with a few of his friends. Passes were booked online for ₹120 and the paper passes had to be collected from the Angamoozhy Forest Office before starting the journey.

We departed from our lodging at 07:00 AM expecting to reach the check-post at 8:30 AM. We had breakfast at a small restaurant along the way and reached the Angamoozhy check-post at exactly 8:30 AM. The paper passes were waiting for us at the checkpost. Here, forest officials carried out a security inspection of our vehicle. All plastic bags, bottles, disposable plates, plastic glasses were counted and recorded in the pass. While leaving Gavi, all these items would be checked and verified at the last check-post. A fine of ₹500 per item would be levied if anything was missing!

This rule is now being strictly enforced in many forest reserves in Kerala. I had noticed the same system while visiting Chembra Peak in Wayanad. This has, definitely helped in reducing litter within the protected forest areas. However, it has not dissuaded irresponsible, anti-social travellers determined to damage nature, from discarding plastic in the jungle. This was very obvious to us as we drove ahead.

There are no restaurants in Gavi. Visitors usually bring their own food with them. At Kochandi check-post, travellers were buying food from a woman selling packed lunches and unniappams. We bought some unniappams to have for lunch, in case we couldn’t find anything else out there in the jungle.

The 35-kilometre stretch from Kochandi to Aanathodu had to be covered by 2:30 PM. Only then could we exit the forest on time. This was to ensure that all visitors exited before 6:00 PM, leaving the forest animals to roam free after dark.

Tourists usually travel to Gavi via the Vandiperiyar – Vallakkadavu route. This was the route I had taken on two of my previous trips as well. But travelling from Kochandi, I realised that the Angamoozhy route was more scenic.

The rest of Kerala may be sweltering in the summer heat, but the valley was still covered in mist at 10:30 in the morning. The atmosphere was pleasantly cool. Our vehicle’s onboard thermometer read 24° C.

Between Kochandi and Aanathodu, I noticed that there was no vehicular traffic from the opposite direction, except a lone vehicle belonging to the Kerala State Electricity Board (KSEB).

At Anathodu checkpost we discovered why. The Aangamoozhi – Gavi route is one-way for private vehicles. Only official vehicles belonging to KSEB and the KSRTC bus ‘Gavi Boy’ are allowed to enter from Aanathodu towards Kochandi.

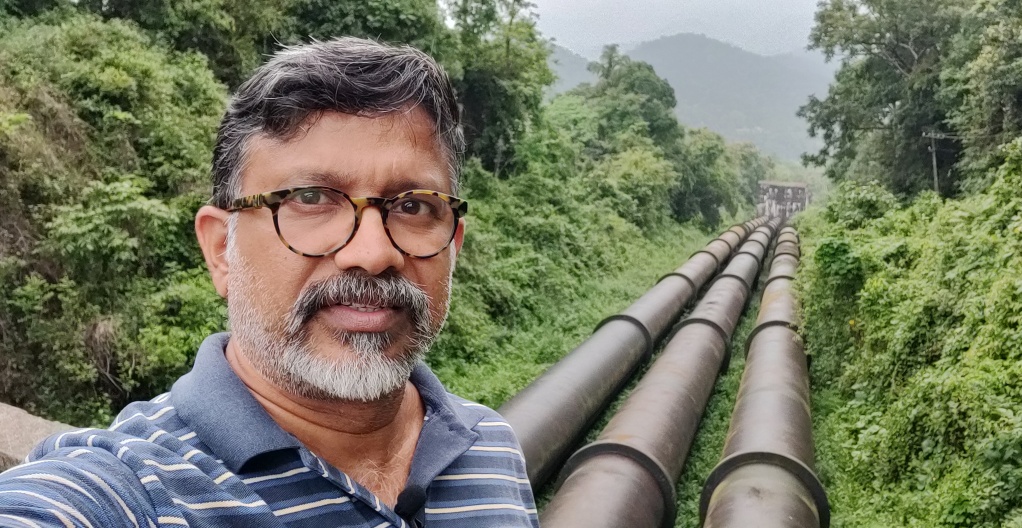

There are quite a few check-posts along this route. Security checks are carried out by the Kerala Police on behalf of KSEB. The driver’s license details, address, total number of travellers etc are recorded at each check-post. Photography is strictly prohibited at the dams. There are a lot of dams enroute – Moozhiyaar, Pampa, Kakki etc – all of which are part of the Shabarigiri Hydroelectric Project. From Kakki Dam, water flows through three huge penstock pipes for hydroelectric power generation. These pipes are mostly underground or tunneled through mountains, and rarely visible. Near Kakki Dam, the origin of the penstock pipes can be clearly seen.

Just before reaching Kakki Dam’s check-post, we noticed a few tribal youth engaged in extracting honey from a rock formation. This was an entirely new experience for me. Previously I had observed honey extraction from honeycombs hanging from trees or buildings. One of the youngsters was perched on the rocks about two metres from ground level. He was removing honeycombs from a cavity in the rocks using his bare hands.

The bees were swarming all over his face and body. The rest of the group were standing close-by as well. None of them seemed even mildly perturbed by the bees. I knew from previous personal experience that a bee sting was no trifling matter. After some hesitation, we left the safe confines of our vehicle and approached them. “Won’t the bees sting?” I asked. Their reply was limited to the nonchalance on their faces. Intense concentration on the job at hand meant that talking was limited to essentials. The honey they were collecting earns them ₹500 per kilogram.

Two of the youth were engaged in squeezing the honeycombs to extract honey into a jar using a leaf as funnel. I tasted the honey with their permission. Tasting newly extracted forest honey while in the forest was a wonderful experience. We captured the process in great detail. Just as we were safely back in our vehicle, the rock covering the cavity collapsed to the ground. The guy who removed the honeycombs had warned the group a few minutes ago “There is a slight issue. That rock is coming loose.” Luckily no one was hurt, and we continued our journey.

Though wild animals stayed away from the road during the day, it was obvious they were moving around at night in large numbers. The sheer amount of elephant dung, some a week old and some still fresh, was proof enough. They were strewn over the road leading from Kochandi check-post. The vegetation in this area is mostly elephant grass and bamboo – both favourite foods of the elephant. So it was no wonder that these were their regular stomping grounds.

Unfortunately, apart from the dung, we were not able to spot any elephants. Going by jungle wisdom, the animals were spotting us before we were anywhere near them, and cautiously staying away due to fear.

The only wild animals we spotted on the journey were a monitor lizard, and a gaur. The gaur dashed across the road less than 5 metres in front of our vehicle. Unfortunately Johar was not filming at that moment, so we missed a chance to photograph the animal. We later retrieved the footage from our vehicle’s dashcam. The monitor lizard was crossing the road at a relaxed pace. I first thought it was a large chameleon. But upon stopping the vehicle, we noted its appearance and size, and realised that it was a monitor lizard. A forest guard who was just behind us on his motorbike, immediately approached us to enquire why we had stopped. We had a sense of being under constant surveillance. Either the animals, or the official protectors of the forest, always had their eyes on us.

Every visit to Gavi reminds me of its Sri Lankan labourers. Lankans who arrived here as refugees 30 years ago, found work in Gavi’s cardamom estates. They played a huge part in Gavi’s growth. However when they retired from service, they were asked to vacate their quarters. Refugees became refuge-less once again. I remember, in 2016, reading some reports about strikes and protests against this eviction,. But, in the hustle and bustle of daily life, I was unable to keep myself aware of the subsequent events. I learnt that some of them now live with their children who were educated and working elsewhere. Some moved to Tamil Nadu, while a few are somehow managing to hold on in Gavi. However, the sympathy of city dwellers like ourselves, who bother with the travails of the downtrodden during occasional exotic trips through forest paths, is clearly unworthy.

At Aanathode check-post, the jurisdiction of Goodrickal Forest Range ends and gives way to Vallakadavu Forest Range. Separate entry fees and camera fees are collected here. We did not have enough small denominations to pay the required ₹130. The check-post had so far cleared only one other vehicle, and therefore they did not have enough money to give small change either. We were saved from this quandary by some youngsters who arrived in a Jeep Compass. They let us have enough money for the pass. We had encountered their vehicle occasionally during the journey. So we were confident that we would be able to return the amount to them at some point during the onward journey.

We had learnt at Aangamoozhy that there was a KSEB canteen (cafeteria) at Kochu Pampa where lunch would be available on pre-booking. However we were not able to find the booking number. Once in Kochu Pampa, the canteen was unmissable. We stopped the vehicle, and enquired if lunch was available. The reply was a question “Do you have a booking?”. But apparently there were a few grains of rice there with our names on them! They agreed to serve us lunch in spite of not calling ahead. The canteen is run by a lady named Molly John. The phone number (8301029951) for booking is clearly displayed on the premises.

For the second time since leaving home for GIE I had a homelike lunch, prepared and served by ‘bangled hands’ (ethnic indian homely women). I was sure that the lunch we had at Onthupacha on Day 3 was also prepared by ‘bangled hands’. Today’s was also an appetizing meal, accompanied by fried and curried fish, three types of stir-fried vegetables etc at a very affordable rate. The fish was freshly caught from the dam’s reservoir. The fried fish was ‘Tilapia’ – they have their own local name for it. However, I was unable to identify the curried fish.

We received our change from the canteen in small notes, and were now in a position to return the money we had borrowed at the check-post. However, while we were having our lunch, the Jeep Compass sped past us. Attempts to attract their attention were to no avail. Could it be that they did not expect the money to be returned? After lunch, we soon found the helpful youngsters again. They were getting ready to eat the packed lunch they had bought from the lady at Kochandi check-post. We returned the money, expressed our thanks, and went on our way.

One of the most alarming things we noted during our journey through Gavi was the plastic waste in the forest. In spite of all the rules and precautionary measures in place, we picked up quite a few discarded plastic bags and bottles. Some of the bottles were accompanied by empty snack packages – apparently discarded by groups who visit the forest for the sole purpose of downing a few drinks. Why do these people who do not understand the importance of forests even bother to travel here? Why can’t they stick to trashing their already dirty urban spaces? Our message to them is the following: “Please leave the forests alone. We don’t think people like you come here to enjoy the forests. Please avoid visiting such places with this attitude”.

There is clearly a need for stricter controls. One possibility is to levy a deposit -say ₹100- per plastic bottle and bag, which can be refunded at the exit point. But there are practical difficulties which make such a scheme impractical in Gavi. The Kochandi – Aanathodu one way traffic restriction being one of them.

Despite all the rules and fines, and regardless of repeated dire warnings from nature, some people will continue to discard plastic wherever they are. We can only try to educate them and hope they will become aware at some point in time. But those of us who genuinely love nature, and want to work against plastic waste, can contribute by picking up discarded plastic from places like these, and disposing of it properly.

There are two main messages we are trying to spread through the Great Indian Expedition. One is against plastic waste and two, afforestation.

We deposited the discarded plastic we collected from the forest, at the check-post. One of the forest guards at the check-post instructed us to leave it at a specific point by the side of the road, and promised to take care of it at the end of the day. Going by the fines stipulated, the trash that we picked up was worth at least ₹ 4500. The forest department should consider installing a large waste bin at the check-post, to collect all the plastic recovered from the forest by environmentally conscious travellers.

The most beautiful part of Gavi is the forest between Kochandi and Aanathodu. Between Aanathodu and Vallakkadavu, the forest is sparse, and does not offer any spectacular views of the valley. Jungles, valleys and dams, all contribute to making Gavi one of the most beautiful forest reserves of Kerala.

As per regulations, the Vallakkadavu check-post had to be crossed before 6:00 PM. However, we passed it well before 3:30 PM. According to our schedule, the day was to end in Kumily and we had already booked a hotel room through the OYO App. Due to our previous unsavoury experience with OYO, we had opted for ‘payment at check-in’ this time. The wonderful aroma of the Jackfruit we bought at Kutralam was wafting throughout the vehicle. And I wondered if any hotel would allow guests to attempt the complex and messy procedure of cutting up a jackfruit, within their premises.

Another day of the Great Indian Expedition’s trial run had drawn to a close.

——————————————————————————–

Read the next part of this travelogue here.

View the YouTube Video of this travelogue here.

Read the original Malayalam text of this travelogue here.

Hear the Malayalam sound track of this travelogue here.