Translated from Malayalam by Liza Thomas

—————————————————————————-

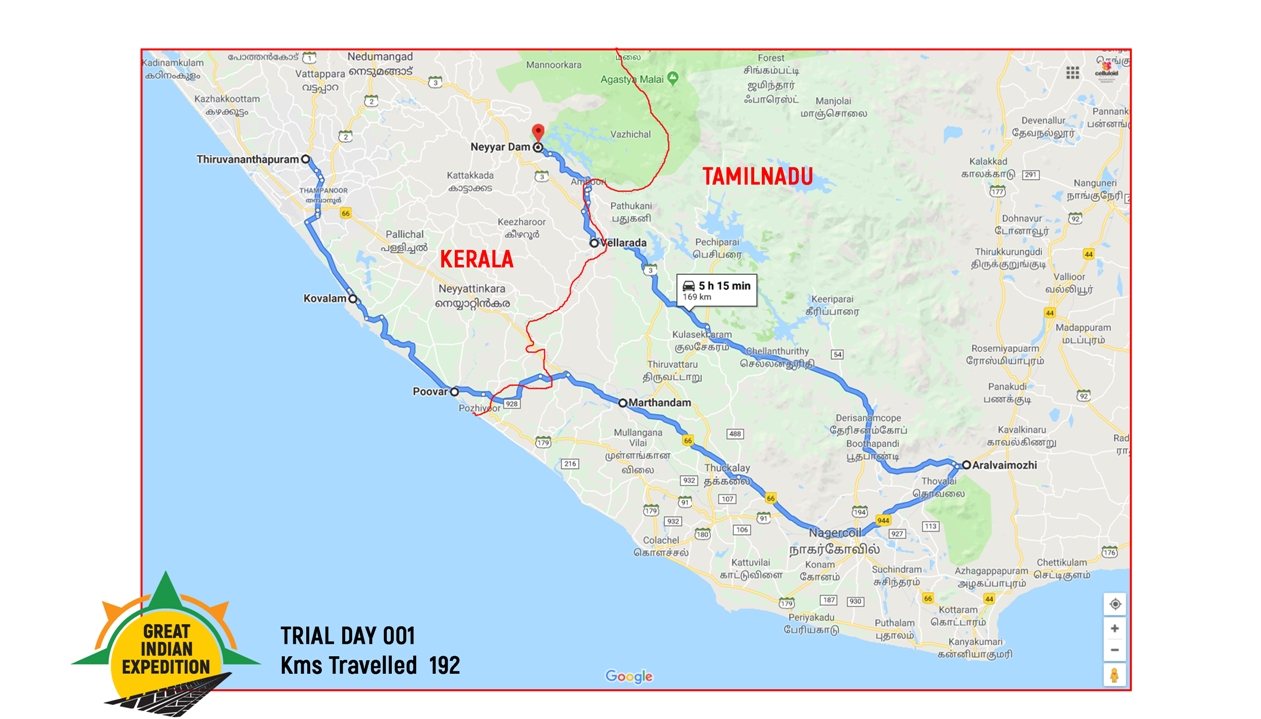

A s a precursor to the Great Indian Expedition, we had planned a trial journey around the Western Ghats, starting from April 22, 2019. This was first postponed to April 27, since the General Elections were announced. At that point of time, cyclone Phani made its way towards us. The weather department’s predictions included heavy rains and landslides in the ghat area, and the journey was postponed to May 2, 2019. After a few more ‘trials and tribulations’, we finally started the journey from Thiruvananthapuram on May 5, 2019.

The idea of a journey encompassing the western ghats was first suggested to me years back, by my engineering classmate Lieutenant Shenoy (Sheshagiri D. Shenoy). But the plans we made for executing the trip just did not take off.

When the Great Indian Expedition was envisaged as a tour covering all of India, over a two year period, we felt a need for a trial journey. And the first option that came to mind was the western ghat route.

Joe Johar, my companion on this trip, has been a friend since the time I started blogging. He will capture the sights and sounds of the journey, edit and upload them for viewing.

The idea was to crisscross the western ghats – up one mountain-pass, down the next, and so on – up until Mangalore. In the process, we would find out if we were indeed ready for the Great Indian Expedition. We would be able to confirm that our physical fitness was up to the mark for such a demanding journey, test all our equipment including cameras and computers, and check if it was actually possible to publish text and video travelogues on a daily basis.

The first task was to figure out which was the first mountain-pass that we needed to cross. After weeding through conflicting information received from various sources, we finally concluded that Maruthwan Mala near Swamithope would be the southernmost ghat and Aralvaimozhi, near Nagercoil, would be the first mountain pass.

We started at J.K. International Hotel behind the Thiruvananthapuram Secretariat at 8 AM. This is meant to be a journey without undue haste. Destinations will be reached whenever they are. The main aim is to be able to see the sights and capture them clearly. More details are available from this link.

The distance from Thiruvananthapuram to Aralvaimozhi is 96 kilometres, via Kovalam, Poovar, Neyyattinkara, and Marthandam. On the way, we decided to stop and explore Oorambu Angady (Angady – local bazaar; usually open air). I had earlier noticed Oorambu Angady on a journey to Kanyakumari as well. Apparently, the Angady existed even at a time when bartering for goods was prevalent, and it is said to be a farmers market where organic and unadulterated produce are sold directly by the grower. However, we did notice that Banganappally Mangoes from Andhra Pradesh were available for sale. So obviously, things were different now.

Once we crossed Kerala border, we found that well-planned over-bridges allowed us to bypass the internal traffic of even smaller towns en route quite easily Once we crossed Marthandam flyover, the western ghats came into view, and gradually the hills lined themselves on either side of the road. We reached Aralvaimozhi at 11:00 AM. It is a small town, and the ghats seemed to spread out in bits and pieces. Vehicles can pass through smoothly, and the path leads right up to Madurai city 254 kilometres away.

A few smaller hills appear to be standing slightly apart by the roadside, miffed with the Sahyan (Sahyan and Sahyadri are vernacular terms used to denote the Western Ghats, literal translation: ‘Benevolent Mountains’). The ghats are not exactly towering here. It was probably because this is an extremely effortless passage between the hills, that we did not find mentions of it anywhere among the mountain passes or forest routes. The road runs wide and smooth, baked by the midday sun. Almost as if to fan sweltering travellers passing along the hot tarmac, huge wind turbines rotate on both sides of the road.

These wind farms stretching all the way to Nagercoil from Aralvaimozhi have also appeared in a few movies. But seeing them on celluloid, or even from a distance, does not give you an idea of exactly how massive they are when viewed from close quarters. I have always been astounded by the sheer size of these things when the blades were being transported by trucks.

We travelled till the ghats vanished behind us, and captured the footage on camera. But I am sure that much better views of the wind farm can be shot in the early hours or late evenings – against the reds and oranges of the twilight sky.

We noticed an Aryaas and went in for lunch. However, we soon found that it was a fake – not a genuine branch of the popular chain of South Indian Restaurants. Trial and error will definitely be the way forward, at least as far as the food department is concerned!

The road through Aralvaimozhi is generously peppered with educational institutions. Most of the engineering and medical colleges, polytechnic institutes, and schools appeared to belong to a group called Rajas. Some of these colleges were apparently examination centers for the NEET (National Eligibility cum Entrance Test – an entrance examination for admission to medical courses), and were crowded with students and their guardians.

As per our plan, we would stop wherever we were at 3:00 PM in order to prepare the day’s travelogues. Now it seems there was still plenty of time left. A 61-kilometer route via Bhoothapandy, Chellanthuruthi, Kulasekharam and Vellarada leads to Nedumangad. We proceeded with the idea that we would halt for the day at Nedumangad, even if it took us till 4:00 PM to arrive. However, in retrospect, there were factors, as yet unknown en route that ensured that this plan too was to no avail.

As soon as we turned towards Nedumangad, we found a lot of brick kilns in the valley. We saw a lot of stacks of unfired bricks, thatched with coconut fronds to prevent exposure to rains. There were thatched sheds near the kilns as well. We went into one of them and requested permission to take photographs. The workers responded that permission should be obtained from the owner – Mr Rajan. I called him and found that he was a fellow Malayali. Permission was instantly granted.

The kiln workers were the ubiquitous ‘Bengalis’ (Bengali: a native of West Bengal state in India. However, the term is loosely used in Kerala to denote migrant labourers from all northern Indian states including West Bengal). Except that these ‘Bengalis’ were actually from West Bengal! A group of 7-8 people including women and children, who were trying to ‘bake’ a better livelihood in a faraway land.

Most of the sights on our path were related to the agriculture of one sort or the other. We encountered groves of everything from coconut and plantain to rubber and cocoa. It is quite possible that these plantations belonged to a Malayali as well. Rubber trees abounded in all stages of growth; right from young – yet to be tapped ones, to mature trees ready for slaughter tapping. We also observed honey bee farming under the rubber trees in some groves.

Topographically, the area was quite similar to Kerala. The fact that it was so green even in summer, made it evident that the area was well irrigated by canals, apart from receiving abundant rain owing to its proximity to the ghats. The roads were in pretty bad shape. Ongoing laying of drinking water pipelines meant that traffic slowed down to a crawl for nearly 30 kilometers.

As we entered a bridge, I noticed a depleted river below. The water level was so low, that rocks on the river bed were clearly visible. We parked our car to take photographs and video. A nearby resident, – a Tamilian, who switched to perfect Malayalam as soon as he discovered that we were from Kerala – apprised us with details of the river. His command over Malayalam was not surprising since this was a border town and people here usually knew both languages well. We learned that this was Palariyar, which emerges from the Perunchani Dam’s reservoir. Palariyar is technically a Marukaal (sluice: a canal used for agricultural purposes) of Perunchani Dam. The depleted flow had caused the water to settle into small pools on the river bed, and women could be seen bathing and washing clothes in them.

We had hardly travelled for two kilometers before we encountered another place of interest, heretofore unknown to us. Most of the signages so far were in Tamil. But at Kalkkalam we saw an English sign which read ‘Thirparappu Water Falls’. Noticing the unusually high traffic in the area, we decided to become part of the crowd. This impulsive decision turned everything topsy turvy for us. As soon as we turned towards the waterfall, we were stuck in a traffic jam. Huge buses and hundreds of smaller vehicles were trying to move up and down a very narrow road. Combined with an absolute dearth of parking spaces, this became quite a serious issue. We were so thoroughly stuck that we could neither go forward nor retreat.

After much struggle, we found a parking space and walked towards the waterfall. We procured entry tickets for ₹5.00 each, and a camera pass for ₹120. There were people everywhere! Both sides of the path were crowded with the usual assortment of hawkers selling cheap trinkets, cosmetics and jewellery, that you would find on most festival grounds in Kerala. I was suddenly reminded of Pinnawala, Sri Lanka where there is an elephant orphanage. The path that the elephants take to their bathing pool, is very similarly lined with shops on both sides. When ‘elephant bath time’ draws near, all these shops would down their shutters to restrain any thieving trunks.

It was clear that river beds in this area were all rocky. When Kodayar river, which flows for 13 kilometers from Pechiparai Dam, reaches Thirparappu, the rocky river bed suddenly turns downward, creating a 15-meter waterfall. Since the river had depleted, the waterfall had thinned down too. It is quite similar to Kutralam (another famous waterfall in south India) except for the fact that here the water appears to have been artificially controlled to create a waterfall; while it happens naturally in Kutralam.

Nearly all of the people who had taken tickets to enter seemed to be rushing to bathe under the falls. One area had been demarcated exclusively for women, while the other was open to all – and both sections were crowded. On another side, there were people trying to swim in a tank smaller than a swimming pool. However, I was firmly convinced that a dip in that dirty water would result in some skin infection or the other.

We learnt a lesson that it was best to avoid such tourist attractions on holidays – we would definitely lose time due to the traffic, and also not be able to appreciate any of the natural beauty because of the crowd. We left the place as soon as we could.

Chittar Dam was the next attraction on our forward path. Though it is designated as a prohibited area, we found many people bathing and taking photographs in the catchment area of the dam. The still water in the reservoir and the surrounding greenery make it a sight for sore eyes in the height of summer. We crossed the dam area and entered Kerala once again.

So far, we had travelled 192 kilometers. Now we needed to find a place to spend the night. Already we had lost 3 precious hours previously demarcated for preparing our travelogue. Driving for another 30 kilometers would take us to Nedumangad where we could search for a room, or we could set up the tent we were carrying along and retire for the night.

Vellarada, from where the road turns to Neyyar Dam, has a lot of Home stays. We called one of them and got a ‘no rooms vacant’ response. Another option was a lodge – but their rooms were so cramped that there was hardly enough space to open up our two laptop computers. Then we discovered a KTDC (Kerala Tourism Development Corporation) motel and turned in for the night. After freshening up, we started to settle in and start work on our travelogues and discovered our new nemesis – extreme fluctuations in the power supply voltage. The situation was so bad, we were convinced that our computers would go haywire. Work could commence only after voltage stabilized hours later, and I finally completed typing out the first draft of this travelogue at midnight.

Not a single thing was completed as per plans. My apologies to everyone who are following the journey closely. The trial trip is actually doing its job – we learnt so many important lessons on day one itself!

Johar was up from early morning, editing footage for our video travelogue, but that will surely take more time to complete. We have not made any concrete plans for the day yet. This is exactly how the journey is going to proceed – without any firm ‘when, where, what and how’. By the time we finish the trial trip, we hope to find a way to publish the text and video travelogues on a daily basis.

Edited by Nishad Kaippally

——————————————————————————————

To read the next part of this travelogue click here.

To view the You Tube video of this travelogue, click here.

To read the original Malayalam text of this travelogue, click here.

To hear the Malayalam sound track of this travelogue click here.